-

Financial reporting and accounting advisory services

You trust your external auditor to deliver not only a high-quality, independent audit of your financial statements but to provide a range of support, including assessing material risks, evaluating internal controls and raising awareness around new and amended accounting standards.

-

Accounting Standards for Private Enterprises

Get the clear financial picture you need with the accounting standards team at Doane Grant Thornton LLP. Our experts have extensive experience with private enterprises of all sizes in all industries, an in-depth knowledge of today’s accounting standards, and are directly involved in the standard-setting process.

-

International Financial Reporting Standards

Whether you are already using IFRS or considering a transition to this global framework, Doane Grant Thornton LLP’s accounting standards team is here to help.

-

Accounting Standards for Not-for-Profit Organizations

From small, community organizations to large, national charities, you can count on Doane Grant Thornton LLP’s accounting standards team for in-depth knowledge and trusted advice.

-

Public Sector Accounting Standards

Working for a public-sector organization comes with a unique set of requirements for accounting and financial reporting. Doane Grant Thornton LLP’s accounting standards team has the practical, public-sector experience and in-depth knowledge you need.

-

Tax planning and compliance

Whether you are a private or public organization, your goal is to manage the critical aspects of tax compliance, and achieve the most effective results. At Doane Grant Thornton, we focus on delivering relevant advice, and providing an integrated planning approach to help you fulfill compliance obligations.

-

Research and development and government incentives

Are you developing innovative processes or products, undertaking experimentation or solving technological problems? If so, you may qualify to claim SR&ED tax credits. This Canadian federal government initiative is designed to encourage and support innovation in Canada. Our R&D professionals are a highly-trained, diverse team of practitioners that are engineers, scientists and specialized accountants.

-

Indirect tax

Keeping track of changes and developments in GST/HST, Quebec sales tax and other provincial sales taxes across Canada, can be a full-time job. The consequences for failing to adequately manage your organization’s sales tax obligations can be significant - from assessments, to forgone recoveries and cash flow implications, to customer or reputational risk.

-

US corporate tax

The United States has a very complex and regulated tax environment, that may undergo significant changes. Cross-border tax issues could become even more challenging for Canadian businesses looking for growth and prosperity in the biggest economy in the world.

-

Cross-border personal tax

In an increasingly flexible world, moving across the border may be more viable for Canadians and Americans; however, relocating may also have complex tax implications.

-

International tax

While there is great opportunity for businesses looking to expand globally, organizations are under increasing tax scrutiny. Regardless of your company’s size and level of international involvement—whether you’re working abroad, investing, buying and selling, borrowing or manufacturing—doing business beyond Canada’s borders comes with its fair share of tax risks.

-

Succession & estate planning

Like many private business owners today, you’ve spent your career building and running your business successfully. Now you’re faced with deciding on a successor—a successor who may or may not want your direct involvement and share your vision.

-

Tax Reporting & Advisory

The financial and tax reporting obligations of public markets and global tax authorities take significant resources and investment to manage. This requires calculating global tax provision estimates under US GAAP, IFRS, and other frameworks, and reconciling this reporting with tax compliance obligations.

-

Transfer pricing

Recognized as a leader in the transfer pricing community, our award-winning team can help you expand your business beyond borders with confidence.

-

Transactions

Our transactions group takes a client-centric, integrated approach, focused on helping you make and implement the best financial strategies. We offer meaningful, actionable and holistic advice to allow you to create value, manage risks and seize opportunities. It’s what we do best: help great organizations like yours grow and thrive.

-

Restructuring

We bring a wide range of services to both individuals and businesses – including shareholders, executives, directors, lenders, creditors and other advisors who are dealing with a corporation experiencing financial challenges.

-

Forensics

Market-driven expertise in investigation, dispute resolution and digital forensics

-

Cybersecurity

Viruses. Phishing. Malware infections. Malpractice by employees. Espionage. Data ransom and theft. Fraud. Cybercrime is now a leading risk to all businesses.

-

Consulting

Running a business is challenging and you need advice you can rely on at anytime you need it. Our team dives deep into your issues, looking holistically at your organization to understand your people, processes, and systems needs at the root of your pain points. The intersection of these three things is critical to develop the solutions you need today.

-

Creditor updates

Updates for creditors, limited partners, investors and shareholders.

-

Governance, risk and compliance

Effective, risk management—including governance and regulatory compliance—can lead to tangible, long-term business improvements. And be a source of significant competitive advantage.

-

Internal audit

Organizations thrive when they are constantly innovating, improving or creating new services and products and envisioning new markets and growth opportunities.

-

Certification – SOX

The corporate governance landscape is challenging at the best of times for public companies and their subsidiaries in Canada, the United States and around the world.

-

Third party assurance

Naturally, clients and stakeholders want reassurance that there are appropriate controls and safeguards over the data and processes being used to service their business. It’s critical.

-

Assurance Important changes coming to AgriInvest in 2025AgriInvest is a business risk management program that helps agricultural producers manage small income declines and improve market income.

Assurance Important changes coming to AgriInvest in 2025AgriInvest is a business risk management program that helps agricultural producers manage small income declines and improve market income. -

Tax alert Agricultural Clean Technology ProgramThe Agricultural Clean Technology Program will provide financial assistance to farmers and agri-businesses to help them reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

Tax alert Agricultural Clean Technology ProgramThe Agricultural Clean Technology Program will provide financial assistance to farmers and agri-businesses to help them reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. -

Tax alert ACT Program – Research and Innovation Stream explainedThe ACT Research and Innovation Stream provides financial support to organizations engaged in pre-market innovation.

Tax alert ACT Program – Research and Innovation Stream explainedThe ACT Research and Innovation Stream provides financial support to organizations engaged in pre-market innovation. -

Tax alert ACT Program – Adoption Stream explainedThe ACT Adoption Stream provides non-repayable funding to help farmers and agri-business with the purchase and installation of clean technologies.

Tax alert ACT Program – Adoption Stream explainedThe ACT Adoption Stream provides non-repayable funding to help farmers and agri-business with the purchase and installation of clean technologies.

-

Builders And Developers

Every real estate project starts with a vision. We help builders and developers solidify that vision, transform it into reality, and create value.

-

Rental Property Owners And Occupiers

In today’s economic climate, it’s more important than ever to have a strong advisory partner on your side.

-

Real Estate Service Providers

Your company plays a key role in the success of landlords, investors and owners, but who is doing the same for you?

-

Mining

There’s no business quite like mining. It’s volatile, risky and complex – but the potential pay-off is huge. You’re not afraid of a challenge: the key is finding the right balance between risk and reward. Whether you’re a junior prospector, a senior producer, or somewhere in between, we’ll work with you to explore, discover and extract value at every stage of the mining process.

-

Oil & gas

The oil and gas industry is facing many complex challenges, beyond the price of oil. These include environmental issues, access to markets, growing competition from alternative energy sources and international markets, and a rapidly changing regulatory landscape, to name but a few.

Updated: January 8, 2025

Despite recent uncertainty, individuals, trusts, and corporations should plan to include a greater portion of their capital gains in their taxable income. The CRA has confirmed that it plans to administer the change for capital gains realized on or after June 25, 2024 based on the proposed legislation.

Parliament prorogation causes uncertainty

On January 6, 2025, Justin Trudeau announced his plans to step down as Prime Minister and the Governor General prorogued Parliament until March 24, 2025. This created uncertainty in our tax landscape, most notably, how this will impact the proposed increase in the capital gains inclusion rate. On January 7, 2025, the CRA confirmed it will administer the changes to the capital gains inclusion rate based on the proposed legislation, despite parliament prorogation. This means it will apply the new 66.67% inclusion rate even though the related legislation hasn’t been enacted.

The proposed increase to the capital gains inclusion rate has widespread impacts and the Parliament prorogation creates greater uncertainty. Reach out to your tax advisor to assess how these proposals and the current uncertainty might affect you, your trust, or your corporation.

Proposed changes

The federal government approved a Notice of Ways and Means Motion (NWMM) to introduce legislation for the capital gains inclusion rate change on June 11, 2024, and released additional technical amendments in August and September 2024. We’ll update this article with any further developments.

For corporations and most trusts, 66.67% of capital gains realized on or after June 25, 2024 would need to be included in income for tax purposes (up from 50%). For individual taxpayers, the increased rate would only apply to the portion of capital gains that exceed $250,000. Capital gains under the $250,000 threshold realized by an individual either directly or indirectly through a trust or partnership will remain subject to the 50% inclusion rate each year. Graduated rate estates (GREs) and qualified disability trusts (QDTs) would also be eligible for the $250,000 threshold available to individuals. This would apply to capital gains taxed in the trust rather than allocated out to beneficiaries.

Transitional rules

For tax years that include June 25, 2024 (i.e., the transition year), two different basic inclusion rates would apply. The inclusion rate that is generally applied to capital gains (or capital losses) throughout the year will be as follows:

For corporations and trusts (other than GREs and QDTs), this effectively provides a blended inclusion rate throughout the year but preserves the 50% inclusion rate in Period 1 and the 66.67% inclusion rate in Period 2. For individuals (including GREs and QDTs), a blended rate would also apply; these taxpayers are entitled to the 50% inclusion rate for all dispositions in Period 1 and are also entitled to the 50% inclusion rate for the first $250,000 of capital gains in Period 2.

Example 1: If a Canadian private corporation (Canco A) had a net capital gain of $400,000 in Period 1 and a net capital gain of $600,000 in Period 2, the capital gains inclusion rate for the year would be a blended rate of 60% (i.e., 50% on the $400,000 in Period 1 and 66.67% on the $600,000 in Period 2). Canco A’s taxable capital gain would be $600,000.

Example 2: If a Canadian individual (Individual A) had a net capital gain of $400,000 in Period 1 and a net capital gain of $600,000 in Period 2, the capital gains inclusion rate for the year would be a blended rate of 55.83% (i.e., 50% on the $400,000 in Period 1, 50% on the first $250,000 in Period 2, and 66.67% on the remaining $450,000 in Period 2). Individual A’s taxable capital gain would be $558,333.

In this scenario, whichever period has the higher absolute value will determine which inclusion rate to use. If Period 1 has the higher amount, the capital gains inclusion rate would be 50%. If Period 2 has the higher amount, it will be 66.67%. This transitional rule essentially ignores the different inclusion rates for Period 1 and Period 2.

Example 1: If a Canadian private corporation (Canco B) had a net capital gain of $400,000 in Period 1 and a net capital loss of $200,000 in Period 2, the capital gains inclusion rate would be 50%, since the capital gain in Period 1 is the higher absolute value. Canco B’s taxable capital gain would be $100,000. If Canco B had a net capital loss of $200,000 in Period 1 and a net capital gain of $400,000 in Period 2, the capital gains inclusion rate would be 66.67%, since the capital gain in Period 2 is the higher absolute value. Canco B’s taxable capital gain would be $133,333.

Example 2: If a Canadian individual (Individual B) had a net capital gain of $400,000 in Period 1 and a net capital loss of $200,000 in Period 2, the capital gains inclusion rate would be 50%, since the capital gain in Period 1 is the higher absolute value. Individual B’s taxable capital gain would be $100,000.

Net capital loss carry-back

If the capital gains inclusion rate for the year that the net capital loss is generated is different from the inclusion rate for the year that it’s applied, the amount of the net capital loss will be adjusted to reflect the inclusion rate for the year in which it’s applied. For example, if a taxpayer generates a net capital loss in 2025 (66.67% inclusion rate) and carries it back to reduce taxable capital gains in 2023 (50% inclusion rate), the net capital loss will be deducted in 2023 at the 50% inclusion rate.

Capital dividend account

The capital dividend account (CDA) keeps track of the non-taxed portion of capital gains realized by Canadian private corporations. When there is a balance in the account, a corporation can pay out an amount not exceeding the balance as a capital dividend. Canadian-resident shareholders can then receive this capital dividend tax free. Any amounts that were added to the CDA before these rules are enacted will not be altered by the proposed legislation (e.g., the 50% non-taxable portion of any net capital gains for a December 31, 2023 fiscal year would not be retroactively affected).

Transitional rule for CDAs

A transitional rule, proposed in the August technical amendments, applies the 50% capital gains inclusion rate for dispositions occurring before June 25, 2024, and 66.67% for dispositions occurring after June 24, 2024. This proposed transitional rule provides certainty on the amount and timing of CDA additions. Without this transitional rule, the inclusion rate applied to capital gains or losses for the CDA wouldn’t be known until the end of the fiscal year including June 24, 2024. Additional transitional rules for CDAs were introduced to provide for an adjustment at the end of the tax year so that the CDA additions would end up being subject to the blended effective capital gains inclusion rate, as if under the general transitional rules. This will allow taxpayers to pay out capital dividends from their CDA with certainty in the transitional year while also ensuring the CDA balance is neither overstated nor understated at the end of the year when considering the general inclusion rate for the transitional year.

Similar to net capital losses, the capital gains inclusion rate for amounts in the CDA will depend on when the capital gain is realized.

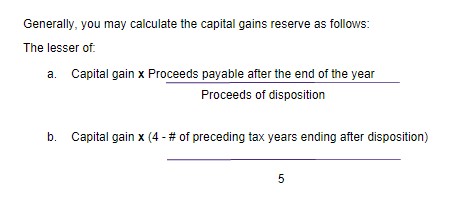

Capital gains reserve

When capital property is sold, a taxpayer may realize a capital gain. Where a taxpayer receives the proceeds from the sale over multiple years, they may be able to claim a reserve to include the capital gain in their income over a period of up to five years.

When a taxpayer claims a reserve to offset a capital gain, the reserve that is claimed must be included in their income for the subsequent year. When the taxpayer claims another reserve in that subsequent year, the difference between the old reserve and the new reserve will be the portion of the capital gain recognized in that subsequent year.

The portion of the capital gain that’s included in income each year will be subject to the inclusion rate that applies for that particular year (i.e., not the inclusion rate that existed in the year the sale occurred).

We believe this could present a problem for sales that occurred before the transition year, and then the taxpayer must determine how much of a reserve (if any) to claim in the transition year. As the prior year reserve is included in the current year’s income, it’s unclear whether the income inclusion occurs before or after the change in the inclusion rate.

The draft legislation proposes that, in a tax year that includes June 25, 2024, the prior year reserve is deemed to be included in income on the first day of that tax year (i.e., at the 50% inclusion rate). Therefore, it’s important to consider whether to forego the reserve in this transition year and realize the remaining capital gain not yet recognized at the 50% inclusion rate. Individuals should also consider whether a reserve coming into income in a future year will be less than $250,000 (net of any other capital gains or losses expected in that future year) in which case the individual may still be able to benefit from the 50% inclusion rate.

Employee Stock Options

The government has proposed to amend the deduction available to employee stock options to tax a taxable benefit at the same effective rate as capital gains under the proposed change to the inclusion rate. Specifically, the deduction available will now be 33.33% of the taxable benefit (i.e., a 66.67% net inclusion) for taxable benefits realized after June 24, 2024. Further, taxpayers can utilize any portion of the annual $250,000 threshold in place of capital gains to claim a 50% deduction on the taxable benefit (i.e., a 50% net inclusion).

Note that this amended deduction presents uncertainty as to the withholding tax obligation of the employer at exercise of the stock options that generally qualify for the deduction as the employer will not know whether the employee’s taxable benefit is reduced by 50% (if the $250,000 annual limit is utilized) or 33.33%. Until the government provides more clarity, we recommend a more conservative approach—to base the withholding tax on 66.67% of the option income for qualifying stock options after June 24, 2024.

Background on employee stock options

A corporation may grant stock options to their employees as a form of compensation. These stock options typically give the employee the right to acquire a security of their employer at an agreed upon price and date. Stock options granted to an employee may result in a taxable benefit for that employee. The taxable benefit will be calculated as the difference between the fair market value (FMV) of the securities when the employee acquired them and the amount the employee acquired them for (i.e., exercise price). Generally, the taxable benefit is included in the employee’s net income in the same year the options are exercised. However, under certain conditions, the taxable benefit is deferred until the year the employee disposes of the shares. Whether the taxable benefit is included when the options are exercised or when the shares are disposed of, there could be a deduction along with the benefit. For example, where the option was granted at an exercise price of at least the FMV of the shares at grant, and the shares subject to the options qualified as prescribed shares, the deduction will be 50% of the taxable benefit. This allows the benefit to be taxed at the same effective rate as capital gains.

Contact your local advisor or reach out to us here.

Disclaimer

The information contained herein is general in nature and is based on proposals that are subject to change. It is not, and should not be construed as, accounting, legal or tax advice or an opinion provided by Doane Grant Thornton LLP to the reader. This material may not be applicable to, or suitable for, specific circumstances or needs and may require consideration of other factors not described herein.

Get the latest information in your inbox.

Subscribe to receive relevant and timely information and event invitations.